- #CONTRAPTION MAKER PACKING UP FULL#

- #CONTRAPTION MAKER PACKING UP SOFTWARE#

- #CONTRAPTION MAKER PACKING UP CODE#

- #CONTRAPTION MAKER PACKING UP FREE#

Ryan had the basic engine working within a handful of months, whereupon Tunnell and anyone else who was interested could start pitching in to make the many puzzles that would be needed to turn a game engine into a game.

#CONTRAPTION MAKER PACKING UP CODE#

Luckily, all those years Kevin Ryan had spent building all those vehicular simulators for Dynamix provided him with much of the coding expertise and even actual code that he would need to make it.

At its heart, the game, which he would name The Incredible Machine, must be a physics simulator. Still, the machine-construction-set idea never left Tunnell, and, after founding Jeff Tunnell Productions in early 1992, he was convinced that now was finally the right time to see it through. If the latter, there’s certainly no shame in that.

#CONTRAPTION MAKER PACKING UP FULL#

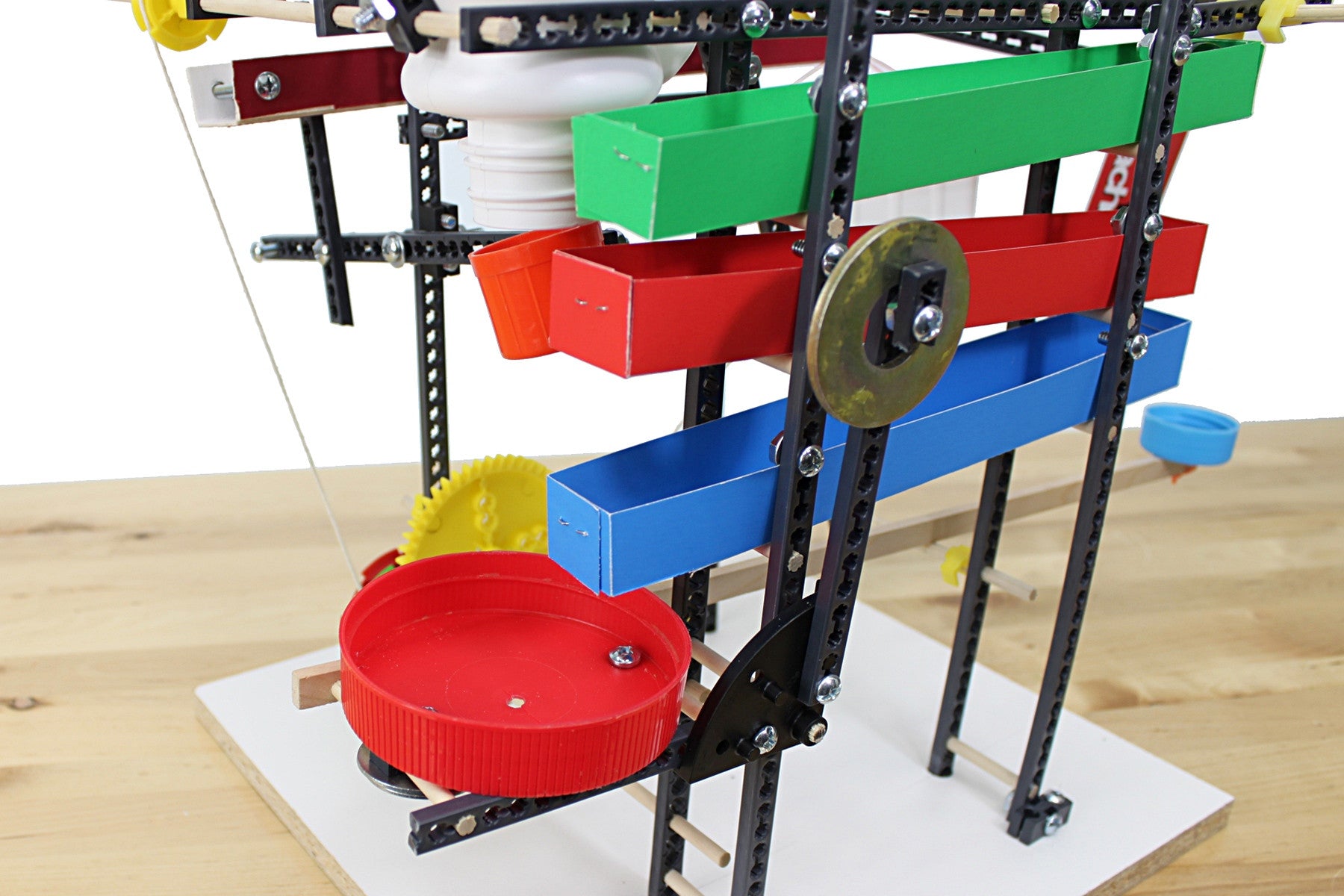

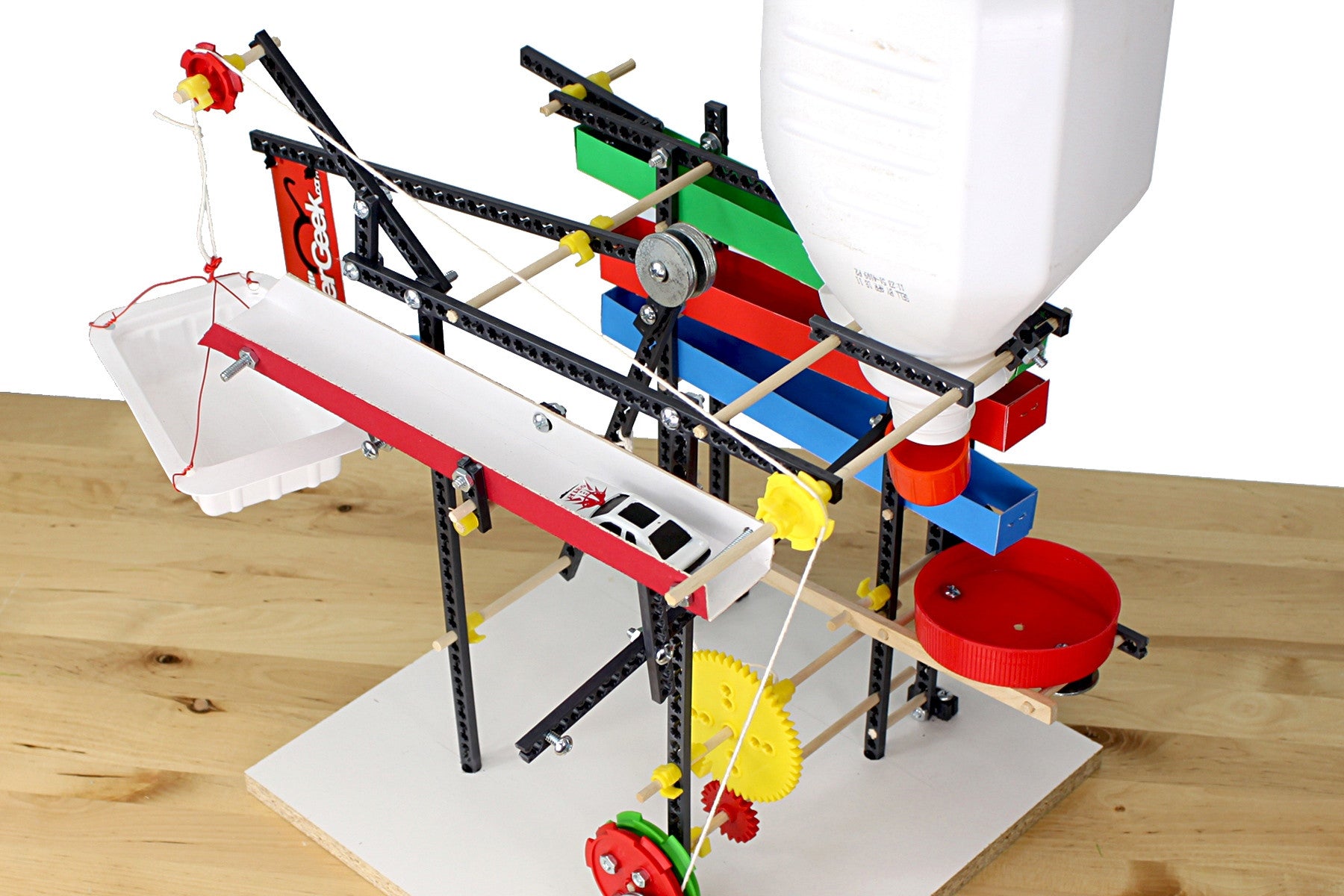

One must assume that Tunnell and Ryan either reinvented much of Creative Contraptions or expanded on a brilliant concept beautifully in the course of taking full advantage of the additional hardware at their disposal. It’s a machine construction set in its own right, one which is strikingly similar to the game which is the main subject of this article, even including some of the very same component parts, although it is more limited in many ways than Tunnell and Ryan’s creation, with simpler mechanisms to build out of fewer parts and less flexible controls that are forced to rely on keystrokes rather than the much more intuitive affordances of the mouse.

#CONTRAPTION MAKER PACKING UP SOFTWARE#

But this blog’s friend Jim Leonard has since pointed out the existence of a rather obscure children’s game from the heyday of computerized erector sets called Creative Contraptions, published by the brief-lived software division of Bantam Books and created by a team of developers who called themselves Looking Glass Software (no relation to the later, much more famous Looking Glass Studios). That, anyway, is the story which both Jeff Tunnell and Kevin Ryan tell in interviews today, which also happened to be the only one told in an earlier version of this article.

#CONTRAPTION MAKER PACKING UP FREE#

But they never could sell the vaguely defined idea to a publisher, thus going to show that even the games industry of the 1980s maybe wasn’t quite so wild and free as nostalgia might suggest. Tunnell and Slye’s idea was for a sort of machine construction set: a system for cobbling together functioning virtual mechanisms of many types out of interchangeable parts. At that time, Electronic Art’s Pinball Construction Set, which gave you a box of (virtual) interchangeable parts to use in making playable pinball tables of your own, was taking the industry by storm, ushering in a brief heyday of similar computerized erector sets Electronics Arts alone would soon be offering the likes of an Adventure Construction Set, a Music Construction Set, and a Racing Destruction Set. In fact, he and Damon Slye had batted it around when first forming Dynamix all the way back in 1983. It was, appropriately enough, an idea that dated back to those wild-and-free 1980s. Tunnell knew exactly what small but innovative game he wanted to make first. So, he recruited Kevin Ryan, a programmer who had worked at Dynamix almost from the beginning, and set up shop in the office next door with just a few other support personnel. If Tunnell hoped to innovate, he had come to believe, he would have to return to the guerrilla model of game development that had held sway during the 1980s, deliberately rejecting the studio-production culture that was coming to dominate the industry of the 1990s.

In the world of movies, and now increasingly in that of games as well, smaller, cheaper projects were usually the only ones allowed to take major thematic, formal, and aesthetic risks. When he stepped down from his post at the head of Dynamix in order to found Jeff Tunnell Productions and make smaller but more innovative games, he was making the sort of bargain with commercial realities that many a film director had made before him. How ironic, then, that in at least one sense comparisons with Hollywood continued to ring true even after he thought he’d consigned such things to his past. As we saw in my previous article, Jeff Tunnell walked away from Dynamix’s experiments with “interactive movies” feeling rather disillusioned by the whole concept.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)